GLASS Review: Shyamalan Nearly Breaks His Own Comeback

Coming off a long string of poorly received flops, M. Night Shyamalan seemed to emerge reborn into audience’s good graces with the genuine surprise of Split. Boasting a unique hook in its central antagonist - a man with 23 different personalities, all performed compellingly chameleonic by James McAvoy - and a welcome simplicity granted by its contained setting and resourcefully compact structure, the film seemed to play more directly with horror elements than the idiosyncratic writer/director has done in the past. Split was also an undeniably Shyamalan product, complete with awkwardly wordy and explanatory exposition, weirdly specific details, and deliberately paced - perhaps flat, if we wanted to be ungenerous - performances that have marked him for ridicule. But the film also seemed to be leaning into those elements in a manner that rendered their inclusion refreshingly self-aware, creating a fun, camp atmosphere whose willful weirdness became a strength. It seemed that Good Shyamalan had returned.

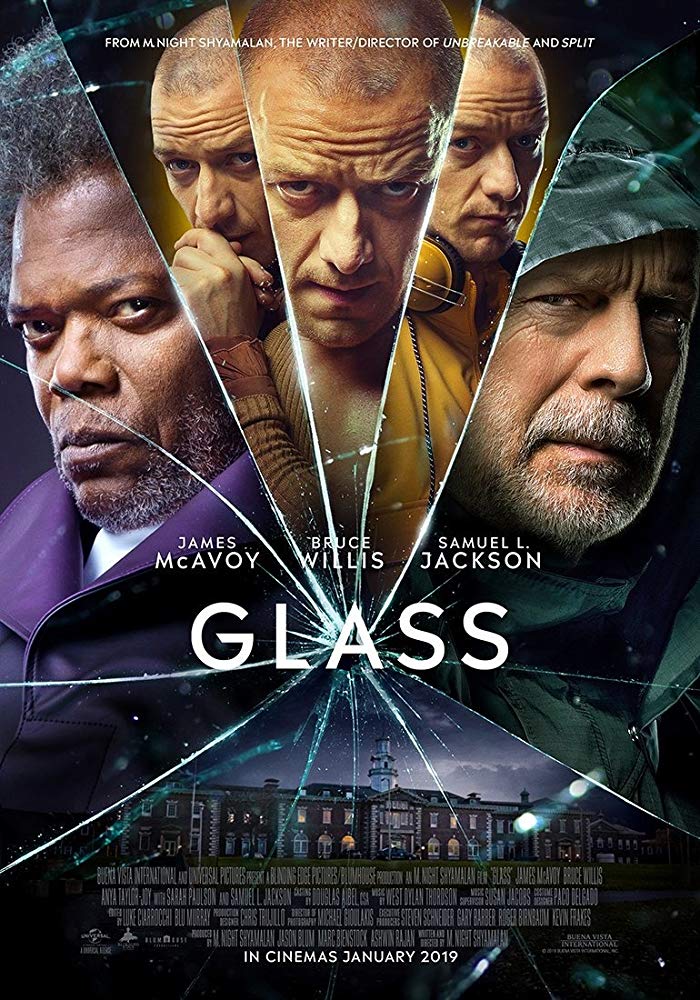

As the mere existence of Glass constitutes a spoiler for Split in its own right, I feel no shame in disclosing that film’s final Shyamalan-ism. In one of his patented twists, Split concludes with the revelation that Bruce Willis’ David Dunn, the protagonist of one of the director’s most beloved films Unbreakable, also inhabits this film’s world. The reveal immediately spurred imaginations for what could be set up to come next, with a comic-book style face-off/villain team-up being the most likely - and exciting - prospect.

Glass promises that very concept at the least in its set-up. Picking up with the physically invulnerable David Dunn, who has continued to don his rain slicker as a vigilante superhero called The Overseer in the years since Unbreakable, the story puts Dunn on a collision course with Kevin (McAvoy) and his various personalities. A portion of those personalities have conspired together in service of a 24th superpowered personality called The Beast. After rescuing a new group of kidnapped girls from The Beast and his Horde, Dunn and Kevin are captured and institutionalized in a mental hospital, where an ambitious psychologist (Sarah Paulson) aims to study and “cure” them. The doctor believes that Dunn and Kevin are suffering from a delusion in which they believe themselves to be superheroes with unique abilities, and that they can be convinced of their notions as being false.

Their incarceration brings the two newfound foes into the proximity of Elijah Price (Samuel L. Jackson), the man revealed to be the villain at the end of Unbreakable who goes by the moniker of Mr. Glass. Price has been held in the institution for years since the discovery of his engineering of mass tragedies, having done so with the intent to create individuals like David Dunn. Confined to a wheelchair on account of his uniquely fragile bones and sedated due to his supposedly advanced, dangerous intelligence, his own delusions are subject to study as well. And upon discovering Dunn’s presence and the existence of The Beast, Price begins to hatch a scheme to further test his own theories around the existence of superheroes.

Director:

M. Night Shyamalan

Starring:

Bruce Willis

James McAvoy

Samuel L. Jackson

Sarah Paulson

Anya Taylor-Joy

Spencer Treat Clark

Screenplay by

M. Night Shyamalan

Mr. Glass was one of the more intriguing components of Unbreakable‘s deconstruction of superhero myth, creating a compelling counterpoint to its protagonist that engaged in a distinctly unique psychology regarding his condition. The film was legitimately ahead of its time, speaking in dialogue with a genre that barely even existed at the time of its release. If anything, the recent domination of comic book adaptations in Hollywood has improved the film’s standing, and made fans clamoring for a sequel even louder.

It’s hard to say that Glass is the sequel they were hoping for, however. It bears a number of surface similarities, carrying over a deliberate pace in the second act and an overall commitment to grounded realism as its own form of subversion. But in almost every other area Glass feels like a distinctly different animal, full of general ridiculousness and possessing an overall demeanor of merely existing for its own sake. The machinations to bring these characters together once again reek of obligation more than actual thematic necessity, because it’s what movies about characters like this do nowadays. While it’s nice to have Bruce Willis back from his semi-permanent coma of a career, if only so briefly, his version of David here seems to be a completely different person from where we left him. He’s surprisingly gung-ho about his heroics, but also seems remarkably unconcerned with proceedings once he’s been locked away, further given less and less to do as the film progresses beyond punching things. Gone is the meditation that marked the film’s predecessor, replaced with the exact heavy-handed tropes it name-drops even as it indulges them.

Bringing Split into the fold doesn’t help much either. McAvoy is still wonderfully fun as he switches between accents and tones while playing Kevin - it’s also still a stellar physical performance. The film’s most interesting conflicts reside with the internal clashes between his various personalities, but the exploitational components of his solo film don’t mesh well with Dunn’s story. The Beast and his Horde were horror characters, never comic book villains until this movie decided they were, and they don’t work nearly as well in that capacity. This is most evident in the film’s third act, in which wide-angle security footage shows his animal-like movements in their full absurdity. The choice to choreograph and display the clumsy action in this way plays into the script’s deconstructive intent, but also undermines the character’s threat.

The film’s third act also brings back to mind another common trait of Shyamalan’s in underwhelming, twisty conclusions. Glass pulls double-duty on this front. The climax unambiguously spells out its subversion as it goes, and then has the audacity to throw out not just one, but multiple twists that inspire increasingly baffled responses. One such twist settles a tugging criticism that may pervade in the back of your mind up to that point: why is the doctor conducting her research in such an ineffective manner? The answer exonerates the character of stupidity, but in turn condemns the movie. Glass also serves as the sloppily combined third act of an impromptu trilogy. It is not lacking its own weird thrills and fun, but it nevertheless fails to deliver on the promise of its predecessors while retroactively making them both worse. Unbreakable and Split each explored how people process and make sense of their trauma, using their specific genres to do so with unique thoughtfulness. Maybe Shyamalan had nothing new to say about that theme this time, which begs the question of why the movie exists beyond the notion that shared universes are in, audiences care more about story minutiae and intermedia connections than theme, and there’s money to be made. To borrow a phrase from YouTuber Lindsay Ellis, there’s “no meaning, only lore.” It’s the return of the Real Shyamalam, and he remains as frustrating and difficult to dismiss as ever.

Glass is currently playing in theaters everywhere.